Casting Processes

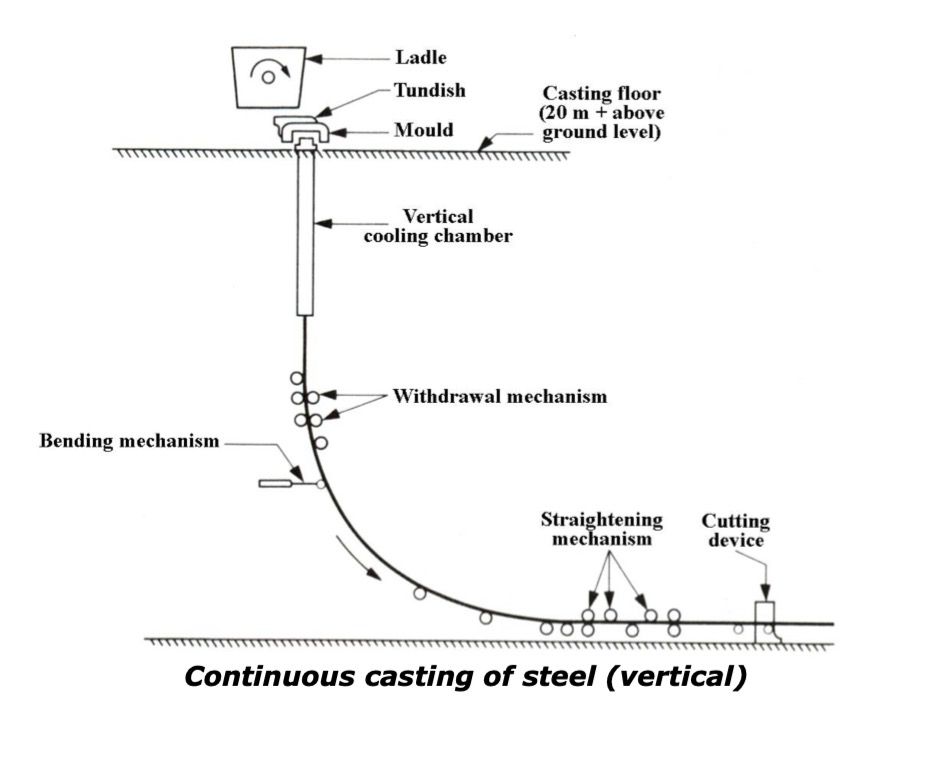

Continuous casting

Also known as ‘concast’, produces continuous lengths of simple shapes which are cut into the required lengths for further processing. Molten metal from a ladle is teemed into a ‘tundish’ which feeds metal into a vertical, open bottom mould. This mould is water cooled copper flux lined and oscillates (to prevent sticking), the molten metal solidifies at the surface of the mould and withdrawn from the bottom. The centre solidifies as it passes through water cooling jets and through rolls to support and curve it into the horizontal plane but has no significant effect on the “as cast” grain structure, it is then flame cut to length. Concast machines may produce several strands simultaneously giving a high production rate. Other advantages include less scrap and greater consistency of quality. Because of the shapes produced it is possible to omit the first stage of rolling that is necessary with ingots. The diagram shows the ladle which is kept at the required temperature whilst being transferred from the steel furnace to its position at the top of the tower structure.

Sand casting

Sand casting is the teeming of molten metal into a mould, where solidification occurs. Almost every finished metal product has been cast at some time during its manufacture, and it may contain evidence of this in its structure, segregation, voids or surface defects.

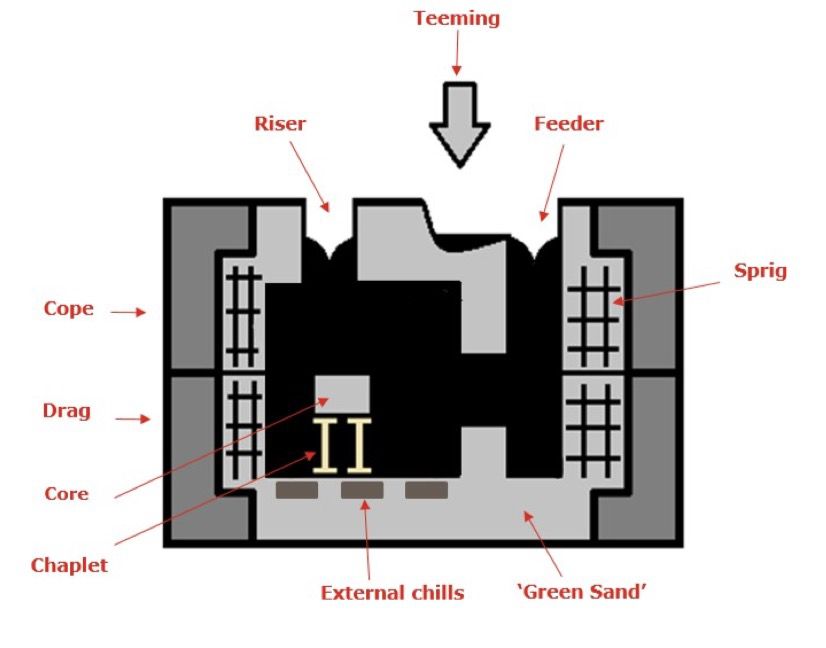

The cavity in the sand is formed by using a pattern (an approximate duplicate of the real part) which are typically made out of wood and sometimes metal. The cavity is maintained by an aggregate housed in a two part box, the top is known as the cope and the bottom is known as the drag.

The mould is made from ‘green sand’ that contains sand, moisture and clay which acts as a binding agent. Too much clay can prevent gases escaping and could cause sever defects such as blow holes.

Dry sand moulds =modified green sand mould, i.e. the skin is dried on the integral mould surfaces, however the mould 30 must be used rapidly afterwards.

Feeders are where the metal is teemed into the mould, of which the shape and dimension is chosen to control and aid uniform flow of the molten metal. A riser is an additional void created in the mould to contain excessive molten material. The purpose of a riser is to act as a reservoir to feed the molten metal back in to the mould cavity as the molten metal solidifies and shrinks, therefore preventing voids in the main casting.

A core, made of sand, is inserted into the mould to produce the internal features of the part such as holes or internal passages. A ‘core print’ is the region added to the pattern that is used to locate and support the core ends within the mould.

Chaplets are stud like supports and are sometimes used to support the bodies of large cores to hold the cores in place, preventing core shift. They are made from the same material as the metal being poured. The heat of the molten metal should melt the chaplets so that they become part of the final casting.

Sprigs are used to provide support to areas that contain large amounts of sand to stop the mould from breaking up. They give the clay something to hold on to and therefore increase the mould wall or core strength. Sprigs are always embedded within the mould or core and never come into contact with the molten metal being cast.

Chills are metal inserts which are generally external to the casting, to help control directional growth and uniform cooling.

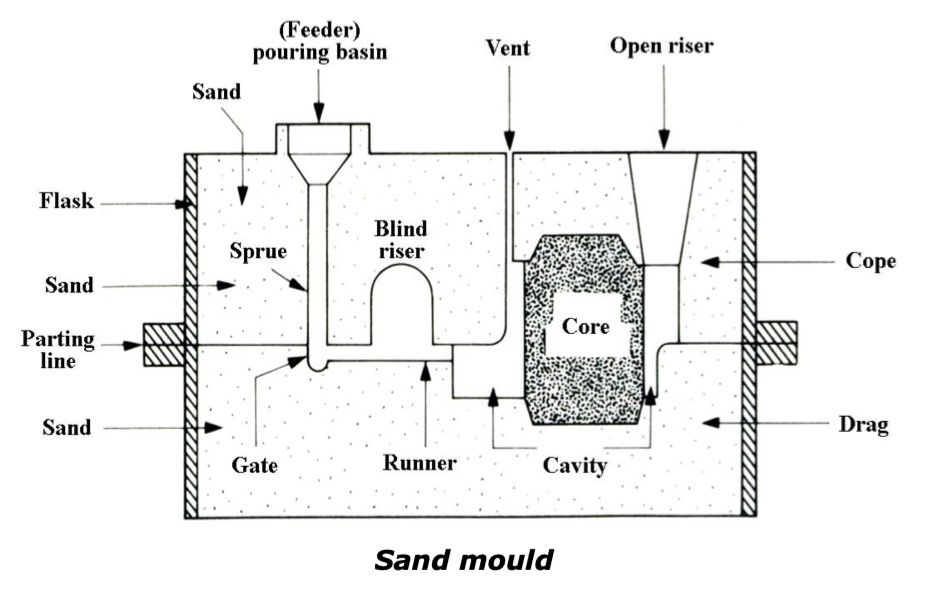

Below is a simple sketch to help understand the setup of a sand mould:

From the tundish or ladle the molten material is poured/teemed in the pouring basin (feeder) which is part of the gating system that supplies the molten material to the mould cavity. The vertical part of the gating system is called the sprue, the horizontal portion is called the runner and the points where it is introduced into the mould are called gates. Additionally, extensions to the gating system are called vents that provides a path for the build-up of gases and displaced air to be vented to the atmosphere.

Generally, the casting cavity is usually made oversized to allow for the metal contraction as it cools down to room temperature. For iron this is due to the change in crystal structure from BCC to FCC as temperature increases, and then reverting back to BCC on cooling. In which case, it is essential that the pattern is oversized to account for the shrinking. The shrinkage allowances are only approximate, because exact allowances are determined by the shape and size of the casting, different parts of the casting might require a different shrinkage allowance as some materials expand and contract more than others.

Typically the sand casting is in two halves, ‘cope’ is the upper half, and ‘drag’ is the lower half. When the mould is separated, there is sometimes a visible parting line on the surface of the casting, known as fin or finning. The parting line is normally found where the cope and drag separate

On removal of the casting from the mould, the excess material on the casting i.e. feeders, risers and fins, are removed by grinding. This cleaning stage is generally referred to as fettling.

Continuous casting

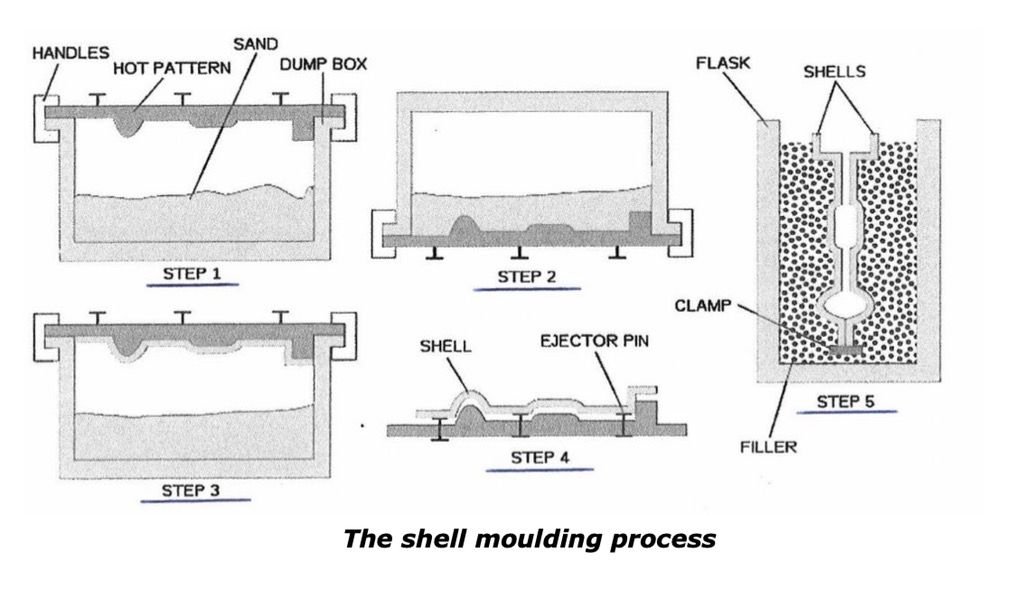

A ferrous or aluminium pattern is made resembling the cast item to be manufactured. The pattern is heated to between 150-370°C and has a coating of silicone applied which acts as a release agent. A fine sand mixed with a thermo-setting binder is then blown over the heated pattern to provide optimum coverage prior to placing into a sand box containing the same material. Further heating is applied to complete resin curing.

The shell is then taken from the pattern in two halves and suitably mounted to receive molten material to produce castings within very fine tolerances.

Notes:

- The skin thickness of the shell is around 3.5mm.

- High capital investment is required, but high production rates can be achieved. The process overall is quite cost effective due to reduced machining and clean-up costs.

- The materials that can be used with shell moulding process are cast irons, aluminium and copper alloys. Typical parts made with this process are connecting rods, gear housings and lever arms.

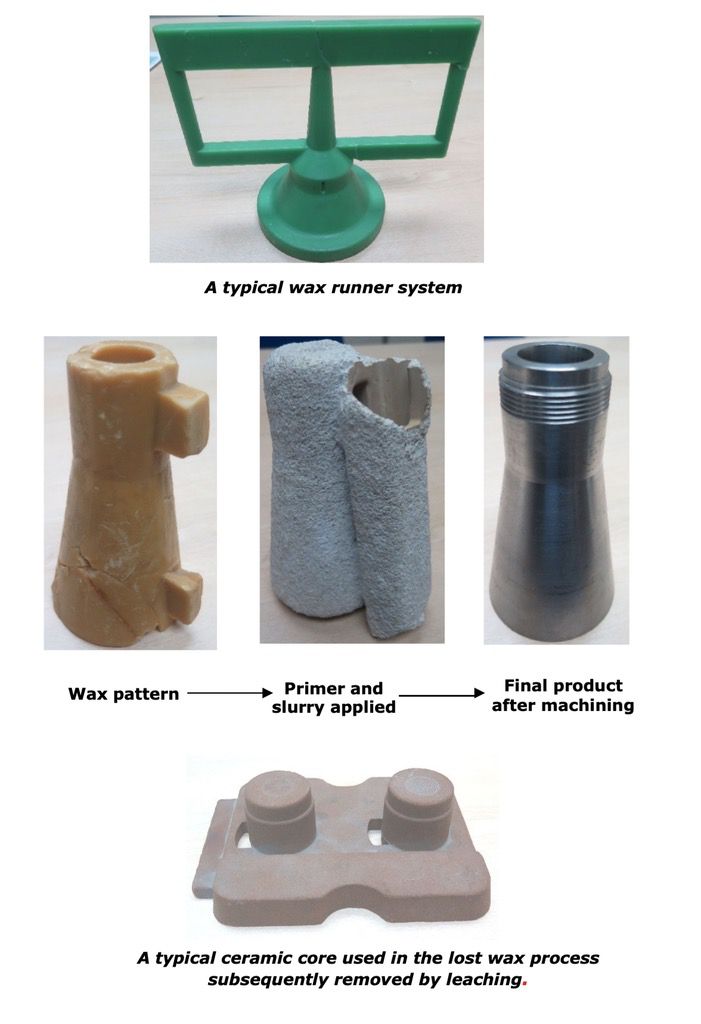

Investment casting

Investment casting is also known as the Lost Wax process. Metals that are hard to machine or fabricate are good candidates for this process and intricate shapes can be made with a high degree of accuracy. However, this process can be costly. This can also be used to make parts that cannot be produced by normal manufacturing techniques, such as turbine blades that have complex shapes or airplane parts that have to withstand high temperatures.

The types of materials that can be cast are aluminium alloys, bronzes, tool steels, stainless steels and precious metals. Parts made with investment castings often do not require any further machining because of the close tolerances and surface finished that can be achieved.

The mould is made by making a pattern using wax or some other material that can be melted away. The wax pattern is dipped in refractory slurry (this process is known as ‘shelling’), which coats the wax pattern and forms a skin. This is dried and the process of dipping in the slurry and drying is repeated until a robust thickness is achieved. The entire pattern is then placed in an oven and the wax is melted away, creating a mould that can be filled with the molten metal. Because the mould is formed around a one piece pattern (which does not have to be pulled out from the mould as in a traditional sand casting process) very intricate parts and undercuts can be made. Internal core passageways are ceramic based and are leached out after the casting cools.

The materials used for the slurry are a mixture of plaster of paris, a binder and powdered silica, a refractory, for low temperature melts. For higher temperature melts, sillimanite an aluminia-silicate is used as a refractory, and silica is used as a binder. Depending on the fineness of the finish desired additional coatings of sillimanite and ethyl silicate may be applied.

The mould thus produced can be used directly for light castings, or be reinforced by placing in a larger container and reinforcing it with more slurry (generally containing zircon sand).

Just before the teeming the mould is pre-heated to about 1000°C (1832°F) to remove any residues of wax and harden the binder. Teeming can be done using gravity, pressure or vacuum conditions. Attention must be paid to mould permeability when using pressure, to allow the air to escape as the teeming is done.

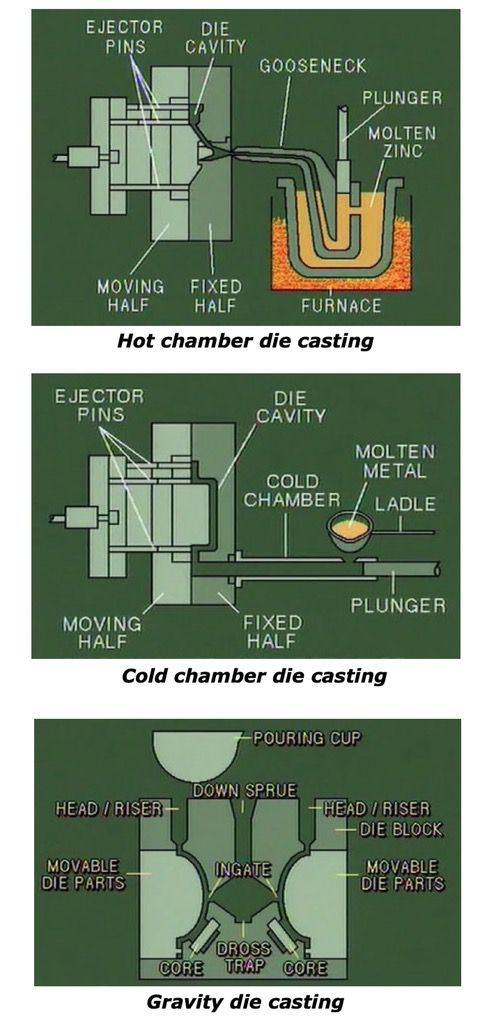

Die casting

The term die casting simply refers to the molten material being forced into the permanent reusable mould under pressure. This process is ideal for large production line runs.

Die casting is primarily used to make castings with aluminium, magnesium alloys and other low melting point materials. The molten metal is forced into the die cavity of special steel dies at pressures between 0.7 - 700 MN/mm².

The following are types of die casting processes:

- Hot chamber process – a piston forces the hot molten metal into the die cavity and maintains pressure until the metal solidifies. Ideal for zinc, tin and lead materials.

- Cold chamber process – molten metal is teemed into a cold piston aperture and then is injected into initially cold die-plates. Ideal for aluminium, magnesium alloys and copper base alloys.

- Gravity die casting process - in this process, the molten metal is not injected into the die but is gravity fed by pouring via a ladle into the feeder head.

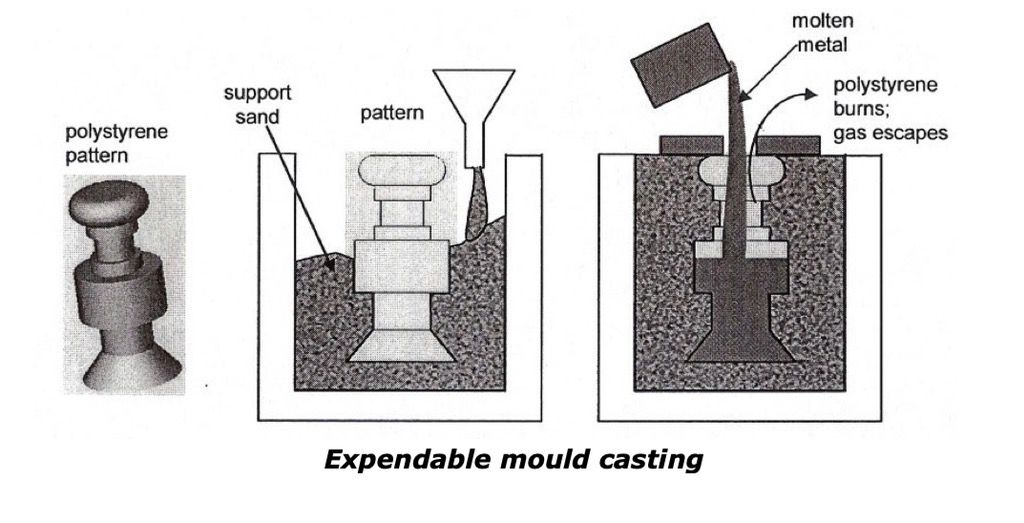

Expandable-pattern casting (lost foam process)

The pattern used in this process is made from polystyrene (this is the light, white packing material which is used to pack electronics inside the boxes). Polystyrene foam is 95% air bubbles, and the material itself evaporates when the liquid metal is teemed on it.

The pattern itself is made by moulding the polystyrene beads and pentane which are put inside an aluminium mould and heated; it expands to fill the mould, and takes the shape of the cavity. The pattern is removed and used in the casting process as follows:

- The pattern is dipped in a slurry of water and clay (or other refractory grains); it is dried to get a hard shell around the pattern.

- The shell-covered pattern is placed in a container with sand for support, and liquid metal is teemed from a hole on top.

- The foam evaporates as the metal fills the shell; upon cooling and solidification, the part is removed by breaking the shell.

The process is useful since it is very cheap, and yields good surface finish and complex geometry. There are no runners, risers, gating or parting lines – thus the design process is simplified. The process is used to manufacture crank-shafts for engines, aluminium engine blocks, manifolds, etc.

*Centrifugal Casting

In centrifugal casting, a permanent mould is rotated about its axis at high speeds (300 to 3000 rpm) as the molten metal is poured. The molten metal is centrifugally thrown towards the outer mould wall, where it solidifies after cooling. The casting is usually a fine grain casting with a very fine-grained outer diameter, which is resistant to atmospheric corrosion, a typical situation with pipes. The inside diameter has more impurities and inclusions, which can be machined away.

Typical materials that can be cast with this process are iron, steel, stainless steels, and alloys of aluminium, copper and nickel. Two materials can be cast by introducing a second material during the process. Typical parts made by this process are pipes, boilers, pressure vessels, flywheels, cylinder liners and other parts that are axisymmetric.